Russell W. Moss slaves: One ‘Herculean’ in size; the other cast out as an ‘old, worn out Negress’

- Mary Lou Montgomery

- Nov 17, 2018

- 6 min read

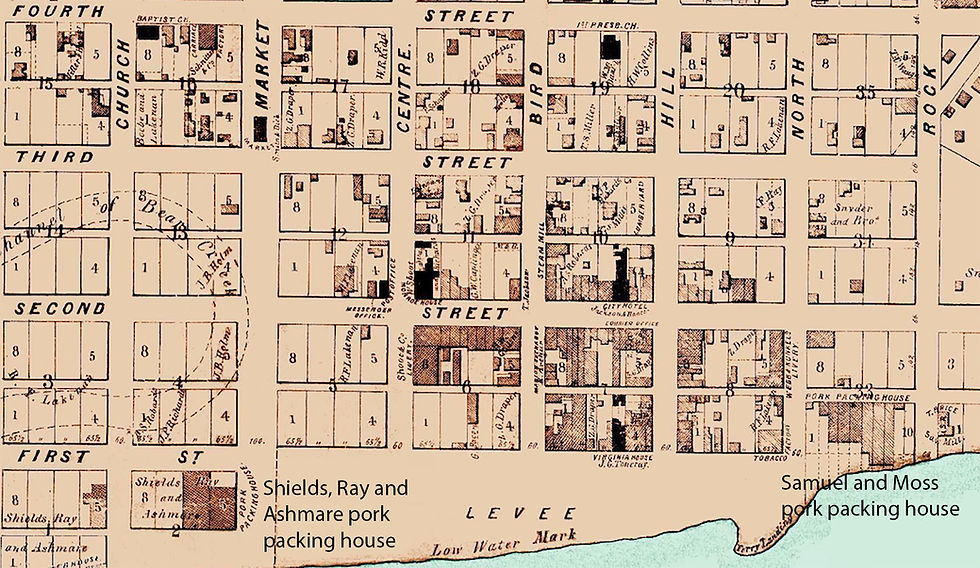

This 1854 map of Hannibal was digitally reproduced by Dave Thomson in 2004. A portion is included here to show the locations of the two major pork packing houses in Hannibal at that time. Both located on the riverfront, the Shields, Ray and Ashmare plant was at the foot of what is now Broadway. The Samuel and Moss plant was located at the foot of North Street.

MARY LOU MONTGOMERY

Feb. 26, 1852, advertisement in the Missouri Courier at Hannibal, Mo.:

“Negroes Wanted.

“The subscribers want to purchase two No. 1 likely young Negro men. None need apply except those who have negroes of good character, as we want them for our own use. The highest cash price will be paid. Apply to SAMUEL & MOSS.”

Hannibal’s population in 1850 consisted of just over 2,000 Caucasians. William Price Samuel, a native of Kentucky, and Russell W. Moss operated a packing company located at the foot of North Street, near the Mississippi River. Both Samuel and Moss were influential in Hannibal’s earliest development.

The Western Union newspaper in Hannibal carried a description of the slaughterhouse building – the largest in Hannibal – and the slaughter operation, in its Nov. 14, 1850 edition:

“The house covers forty thousand feet, and is the largest establishment of the kind in the United States, except the house of Ashbrook, of St. Louis. They can kill and pack 150 bullocks, or 1,500 hogs per day, and with but little trouble can prepare to kill 200 of the former, and 2,000 of the later. They have three large iron tanks, where they can render 50,000 pounds of lard or tallow per day. These tanks are worked by steam, and produce a beautiful article. The lard from this house was pronounced the best lot received in New Orleans, last winter.”

A notice in the Hannibal Journal on March 25, 1852, helps to paint a visual image of the impact that the slaughter house had in Hannibal: “Fine stock: We noticed on Monday, two enormous beeves passing up Main Street. They were raised near West Ely, and were being driven to St. Louis. Their weight, as ascertained by the city weigher, was, of the largest 2,275 pounds; the other 2,270 pounds.”

Slave labor

Louis Butler was born a slave circa 1820. He grew into a stalwart man, standing six-foot-three at his prime and weighing about 250 pounds. At the time of his death in March 1890, the Kansas City Star carried an apt description of this humble man: He stood “straight as an arrow and (was) finely developed. His arm was the size of an ordinary man’s leg.”

Butler worked for the Samuel and Moss slaughter company in Hannibal during the 1850s, and was owned by Russell W. Moss.

Proud of his “possession,” Mr. Moss placed a $1,000 wager that Butler could “cut open and eviscerate (disembowel) more hogs in less time than any man in St. Louis.”

The event was staged. The contest was easily won by “The Hannibal Hercules, who disposed of seven hogs in one minute,” the Milwaukee Sentinel reported in its March 1, 1890 edition, when announcing Butler’s death.

Meanwhile, slaughter and packing house business went on in Hannibal as usual.

In April 1853, a total of 750 “tierces of beef” were shipped on the Jennie Deans, from Hannibal to St. Louis, by Samuel and Moss.

The packing house business at Hannibal reached its peak around 1856, and business dwindled thereafter. By the early 1860s, according to the Consolidated list of all persons subject to military duty, Louis Butler had been sold to R.F. Lakenan, (the subject of this author’s Nov. 3, 2018 story.)

Note: The Jennie Deans was a boat owned by the Keokuk and St. Louis Packet Company, which was often piloted before the Civil War by William Robbins of Hannibal. A “tierce of salt beef” is a cask weighing 280 pounds.

According to the newspaper report of Louis Butler’s death, Dr. Sam H. Anderson treated the patient during his final illness. He said that Mr. Butler had the largest frame he had ever seen.

Mr. Butler was buried in Centropolis, Jackson County, Mo., according to the newspaper report.

Another slave,

a different ending

On Feb. 6, 1862, the Hannibal Daily Messenger took Russell Moss to task in reference to his treatment of another slave, “an old, worn out Negress.”

“There appears to be considerable feeling displayed about town, respecting the circumstances under which, as is alleged, ‘Old Aunt Kitty’ was left by her master, Russell Moss, Esq., to perish and freeze to death. If it is true, as is said, that this old slave was deprived of the necessary comforts to preserve life, by the man who has grown rich on her earnings, it would be fitting that our authorities took action in the case. If we have laws regulating treatment of slaves, this case would seem to us to call for an enquiry into the cause of ‘Aunt Kitty’s’ sudden death. But we forbear further remarks at the present, trusting that the city attorney or the officer whose duty it may be, will enquire into the matter.”

No further mention of this atrocity was found in the digitized editions of this newspaper.

1860

Russell W. Moss 1860 Marion County, 37 slaves.

Female, 70, black

Male, 34, Black

Male, 34, black

Male, 30, black

Male, 30, mulatto

Male, 30, Black

Male, 17, black

Male, 16, black

Male, 12, black

Male, 13, black

Male, 16, black

Male, 6, black

Male, 4, black

Female, 4, black

Female, 35, black

Female, 30, mulatto

Female, 30, mulatto

Female, 20 black

Female, 14, black

Female, 12, black

Female, 11, black

Female, 7, mulatto

Female, 7, mulatto

Female, 12, black

Female, 5, black

Female, 8, black

Unreadable

Female, 5, black

Female, 1, black

Female, 1, black

Female, 1, black

Male, 40, black

Female, 3, black

Female, 55, mulatto

Female, 12, Black

Female, 18, black

Notes

The Consolidated list of all persons subject to military duty during the early 1860s listed Louis (Lewis) Butler, colored, age 42, married, and owned by R.F. Lakenan of Jackson Township, Shelby County. In 1870, a woman named L. Butler is listed as a domestic working in the home of R.F. Lakenan, which was on Broadway in Hannibal, across from what is now the First Christian Church. Other Hannibal Butlers of color listed in the 1870 census were: Maria, 21; George, 13; William, 2; and Mary, 1 month; and Charles, 11. They lived in Hannibal’s first ward, on the date of the census, June 10, 1870.

In 1871, a man of color named L. Butler is listed in the Hannibal city directory as operating a fruit cart in Hannibal. Another man of color of the same era was Ed Butler, who made a living repairing chair bottoms. He was known as ‘Old Hannibal’ and was pictured in a number postcards after the turn of the 20th century. He died in 1909 at his Hannibal home in “Beersheeba,” according to the Quincy Daily Journal of May 20, 1909.

* Kate Ray Kuhn, in her 1963 history book, “The History of Marion County, Missouri,” said that Ed Butler was brought to Hannibal from Kentucky by Dr. Hampton, (also known as John A. Hampton.) Dr. Hampton was the father of Dorcas Hampton, the subject of this author’s historical biography, ‘The Notorious Madam Shaw.” It is a curiosity of this author whether the two Butler men were related.

* The Samuel and Moss establishment was one of two slaughter houses on the banks of the Mississippi River at Hannibal; the second was Shields, Ray and Ashmare, located at the foot of Market (later renamed Broadway). For at least a portion of the decade that Mr. Moss operated the slaughter house in Hannibal, he made his home at 150 Market (Broadway.) The competing meat company was located across the street and a block to the east, on the levee.

By 1870, Russell Moss and his wife had moved back to Shelby County, which Mr. Moss had helped settle prior to the establishment of the county. Mrs. Mary Moss, died in 1886, followed by Russell Moss in 1888. They are buried in Browne Cemetery, Hunnewell, Shelby County, Mo.

William P. Samuel was co-owner of Samuel and Moss Packing Co., the largest and most important industry of Hannibal in the early days, and his wife, Sarah Lavinia, was a daughter of George (Peg-leg) Shannon, youngest member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Research assistance

Research for this story included information from Rhonda Brown Hall, researcher and writer, and moderator of “Old Hannibal” and Negro Family’s Research Center Facebook pages.

Jim's Journey, The Huck Finn Freedom Center, offers resources to those who are interested in building cross-cultural understanding by documenting, preserving and presenting the history of the 19th and 20th-century African American community in Hannibal and northeast Missouri. http://www.jimsjourney.org/ G. Faye Dant is a fifth-generation African American Hannibalian and descendant of Missouri slave, James Walker.

Comments